Manic Pixie Dream Girl

“It’s not my job to make you a better man and I don’t care if I’ve made you a better man. It’s not a woman’s job to be consumed and invaded and spat out so that some man can evolve.”

- Jenny Schecter, The L Word

She is a ray of the sunshine in the dull life of the hero. She walks in with a sprinkle of glitter, smiles all the time, is full of quirks and invests her vintage-clad self completely in changing the hero, and bringing colour into his life. Her name is irrelevant because the story is never about her. Sometimes she can be named after a season, and sometimes a woman in the hero’s past he never got over. This is the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, one of the simultaneously most tiresome and most enduring tropes in cinema.

The Manic Pixie Dream Girl is essentially a free-spirited, positive character with a unique outlook on life, but has no interests or agency of her own, except to improve the hero’s life. The term was coined by film critic Nathan Rabin to describe Kirsten Dunst’s character in Elizabethtown. According to Rabin, “The Manic Pixie Dream Girl exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” This is the fundamental problem with this trope: she is never a real, fleshed-out person in the context of the film. She is always seen through the filtered perception of the hero, and the only parts of her personality that are highlighted are the ones that serve the hero’s purposes.

Though seemingly harmless, the MPDG is in some ways, a more harmful a stereo-typification than the damsel in distress of action movies, because it recognizes that women are intelligent, inspiring, have defined personality traits and ways of looking at life, but implies that all these qualities are best deployed in the service of “saving a man.” It places the woman’s life and interests at a position secondary to the man’s. It is also extremely reductive, because the only things the audience gets to know about these women apart from their affinity for hair dye, their penchant for painting birds on the hero’s gray walls, and their tendency to break into spontaneous dance routines. We don’t know about their hopes, fears, and issues, we don’t know what motivates them, and haunts them, in a nutshell, we don’t know what makes them human. And they aren’t meant to be human, with human failings and imperfections. They’re simply temporary stops on the hero’s journey to a better self, as is seen in 500 Days Of Summer: after Summer, comes Autumn. And the qualities the hero projects on to her are what eventually breaks him. “Yes, Summer has elements of the manic pixie dream girl – she is an immature view of a woman,” says director Webb. “She’s Tom’s view of a woman. He doesn’t see her complexity and the consequence for him is heartbreak.”

The trope has harmful real-world consequences too. The MPDG is an ideal distillation of every unique positive quality a woman must have. It creates, like all tropes do, unrealistic expectations that can be exhausting to live up to. The Manic Pixie Dream Girl is not just an onscreen fantasy–she’s a template for young women’s lives.Fiction creates real life, and women try to behave in ways that they find sanctioned in stories written by men. The constant pressure on women to be cheerful, bubbly and quirky, and to use these attributes to turn a man’s life around is damaging. The ideal urban woman is expected to smile all the time, and not have any issues of her own. While, both in art and in real life, the hero’s shortcomings and less-than-ideal state of life are almost glorified as a canvas on which to paint his tortured self, any signs of the messy puddles of human existence in the woman’s life is met with instant distaste. The MPDG doesn’t allow women to have problems with body image, mental health issues, or troubled pasts. Seeing the idealization of this trope makes it seem as though women must go through life as a caricature of their happiest selves.

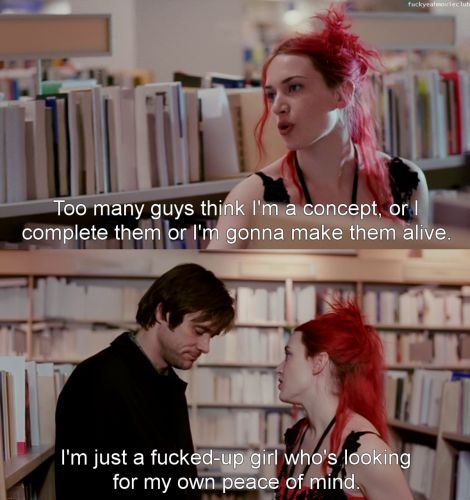

The end of the MPDG would be beneficial, not just for women, but for men too. The Manic Pixie Dream Girl has only one purpose: as a catalyst for male transformation. Both in her real and fictional manifestations, she sends out the message, that the soulful and sensitive young man can only learn to appreciate life by falling in love with a woman who sees the bright colors and we need women who are lead characters and us as an audience deserve to see men who love these women for the complicated and decidedly non-ethereal people they are. Clementine in Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind puts it best, “I’m not a concept. Too many guys think I’m a concept or I complete them or I’m going to ‘make them alive’…but I’m just a girl who’s looking for my own peace of mind. Don’t assign me yours.”